DeepSeek V3.2 Technical Report: DSA, Better Post-Training, and Agent "Generalization"

The Weekly Salt #98

This week, we review:

⭐DeepSeek-V3.2: Pushing the Frontier of Open Large Language Models

Guided Self-Evolving LLMs with Minimal Human Supervision

Only two papers this week. I’m at NeurIPS this week and a bit busy, but next week I’ll publish a report on what I’ve seen there, focusing on broader trends and shifts in the field rather than individual papers that have already been circulating online for a while.

⭐DeepSeek-V3.2: Pushing the Frontier of Open Large Language Models

The paper presents DeepSeek-V3.2, the latest DeepSeek model specifically improved for reasoning and agentic tasks, without blowing up inference cost.

The authors argue that open models have been stuck with inefficient vanilla attention, underpowered post-training, and weak agent generalization. V3.2 is positioned as a counterexample: a sparse-attention architecture that keeps long-context quality, a post-training budget that is a substantial fraction of pretraining, and an agent training pipeline that is deliberately built around verifiable tasks rather than ad-hoc tool use logs. It is very much a “systems and training recipe” paper.

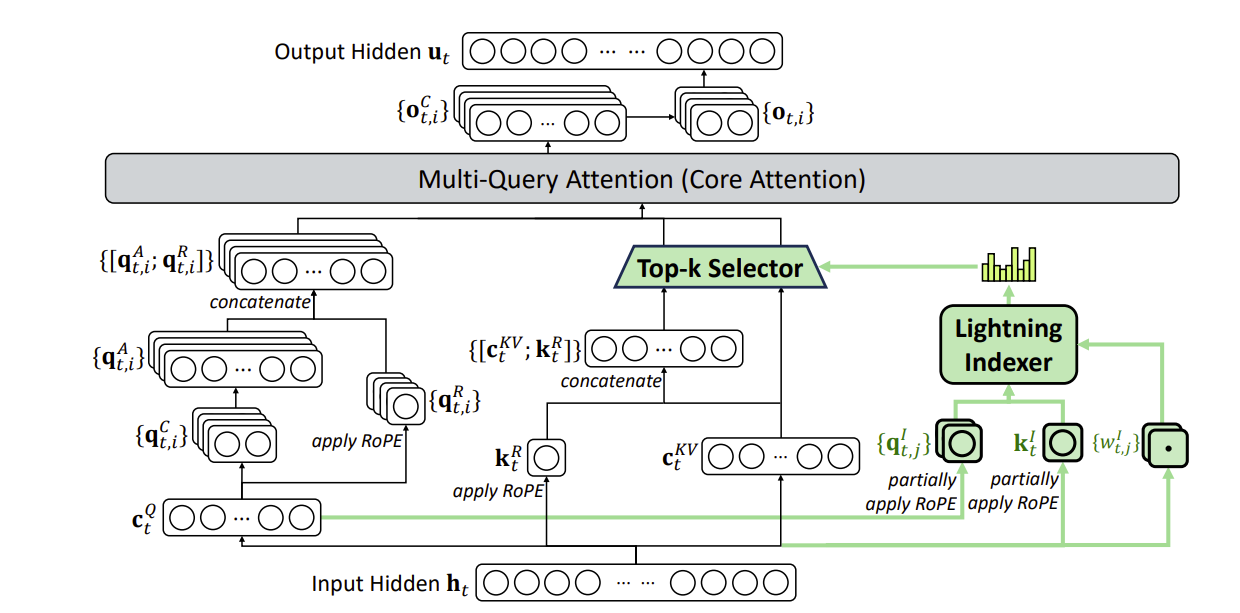

Architecturally, the key change from their previous V3.1-Terminus base is DeepSeek Sparse Attention (DSA). Instead of attending densely over all past tokens, a lightweight “lightning indexer” scores candidate keys and selects a top-k subset for the main attention to operate on. The indexer itself is small, uses few heads, runs in low precision, and is trained in a dense warm-up phase to mimic the full attention distribution before the model is switched to sparse mode and jointly fine-tuned. Because the expensive part of attention is now restricted to a small subset of tokens, they report substantial end-to-end cost reductions for long contexts on production H800 clusters (so, still using their H800s, it seems!), with no measurable loss on standard and long-context benchmarks and even slight gains in some long-context reasoning tests. They also check that ChatbotArena–style human preference scores stay essentially unchanged compared to the dense predecessor, which matters if you believe most sparsity work dies in the gap between synthetic benchmarks and user perception.

On top of this base, the work leans heavily on an enlarged and carefully stabilized RL stack. The authors keep their Group Relative Policy Optimization (GRPO) algorithm, but scale it up both in compute and in engineering detail.

First, they train domain specialists, separate models for mathematics, coding, general logical reasoning, several types of agents, each with both “thinking” and “non-thinking” modes, using large-scale RL. Then they distill those specialists back into a single V3.2 model using supervised learning before running a unified RL stage over reasoning, tool use, and alignment data. To keep such a large RL run from blowing up, they tweak the KL estimator to remove bias, introduce masking of highly off-policy negative trajectories, and freeze Mixture-of-Experts routing paths from sampling to training so the active parameter subspace doesn’t whipsaw between frameworks. The claim is that, taken together, these tricks give a repeatable RL recipe that can safely consume a post-training budget above ten percent of pretraining compute, unusually high by open-model standards.

For search agents, they build a multi-agent pipeline using web tools: one agent samples long-tail entities and constructs queries, several answer-generation agents propose candidate responses, and a verifier with tool access filters for cases where only the ground truth answer is correct. For code agents, they mine issue–pull-request pairs from GitHub, automatically set up runnable environments with dependency resolution, and rely on tests to gate whether a patch truly fixes a bug without regressions, yielding tens of thousands of reproducible coding tasks across many languages. A code-interpreter agent uses Jupyter to solve math and logic problems via execution. Finally, a “general agent” pipeline automatically synthesizes nearly two thousand tool-rich environments, tasks, and verifiers under the constraint that tasks must be hard to solve but easy to check via a programmatic verifier. RL is then run on this suite, with rewards that mix verifiable task success and rubric-based quality scores. On public leaderboards covering reasoning and agent benchmarks, the main V3.2 model clusters near GPT-5 and strong closed models; an extra-compute “Speciale” variant that relaxes length penalties and adds math-heavy data reaches competition-level results in contests like IMO and IOI.

What is this work really saying about where open LLMs are headed? One reading is that architecture is now the least interesting part: DSA is clever but incremental compared to the sheer effort poured into RL stability and agent environments. The big bet here is that you can get competitive reasoning and tool-use behavior from an open stack if you are willing to pay for (a) a serious RL budget, and (b) a sprawling, verifiable synthetic training universe.

DeepSeek also admits they lag proprietary models in breadth of world knowledge and in “intelligence density” (they often need longer chains of thought to reach similar quality).

Guided Self-Evolving LLMs with Minimal Human Supervision

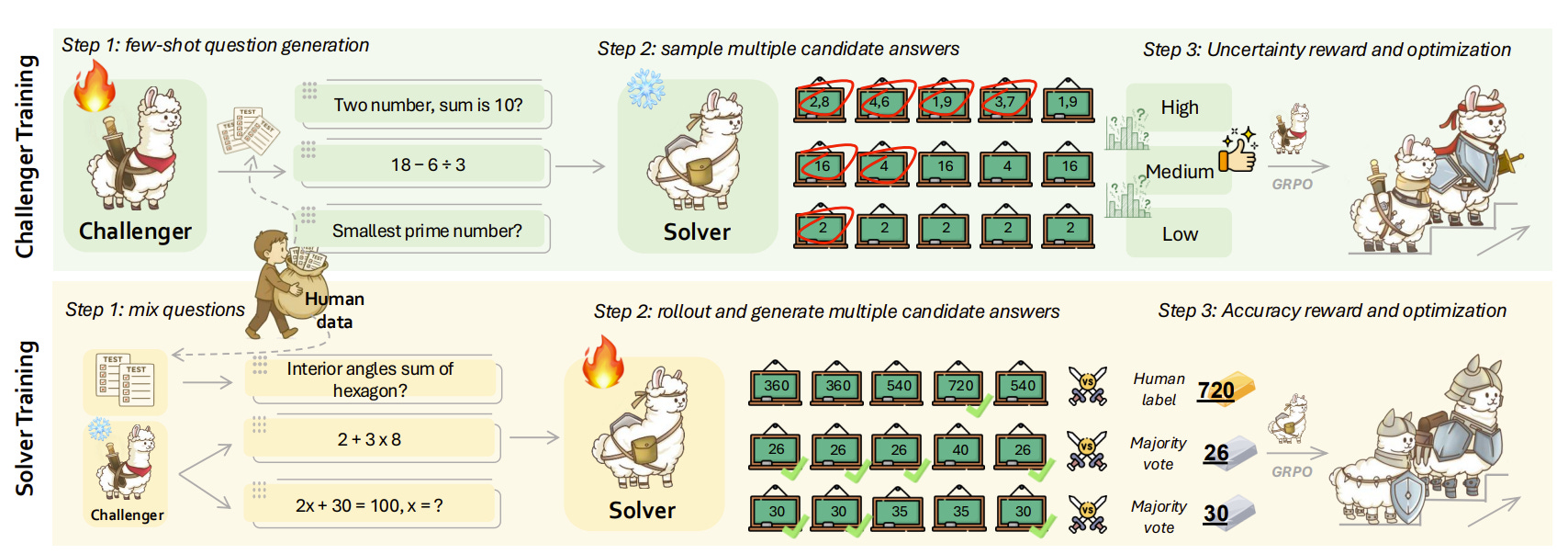

The paper tackles a very specific failure mode of “self-evolving” LLMs: left to their own devices, Challenger–Solver self-play setups like R-Zero quickly plateau, start generating boring or pathological questions, and sometimes even get worse the longer you train them.

The authors argue that this is mostly about concept drift and diversity collapse: the Challenger keeps exploring the same narrow regions of the task space and the Solver learns to game whatever imperfect reward proxy you give it.

They propose R-FEW, a variant of self-play that injects a tiny amount of human supervision as an anchor, while preserving the overall data-free flavor.

Methodologically, the work sits on top of a unified Challenger–Solver formalism for existing self-play systems and then tweaks the Challenger in a fairly surgical way. Instead of generating questions entirely in the void, the Challenger conditions on a small pool of human-labeled “anchor” examples, sampled as zero-to-five in-context demonstrations at each rollout. Sometimes it gets no anchors and behaves like R-Zero or sometimes it sees a few exemplars that subtly pull its generation back toward human-like distributions.

The reward for the Challenger still encourages mid-difficulty questions (roughly “success rate ≈ 50%”), but now includes an explicit term that rewards semantic proximity to the human anchor distribution and a repetition penalty to avoid cycling. A short supervised warm-up ensures the Challenger can reliably follow the fairly complex prompting format.

On the Solver side, R-FEW replaces the naive “train on everything you generated” scheme with an online curriculum that tries to stay in the model’s zone of proximal development. For each synthetic or human question, the Solver runs multiple rollouts, estimates its own success rate, and the training set for the next step is restricted to mid-uncertain items, selected by quantiles (roughly the middle 30–70% band). Both synthetic and human examples go through this filter, and human data is up-weighted to avoid being drowned by synthetic noise. Optimization still uses group-based policy gradients, but the key change is the data pipeline: the Solver is only updated on questions that are neither trivial nor hopeless, and where human anchors get a modest bonus.

Training curves show that R-Zero’s question diversity, measured by n-gram variety, collapses early and later “recovers” only because questions become extremely long! Difficulty apparently rises, but much of that is verbosity-induced rather than conceptual. R-FEW keeps both length and diversity in a narrower, more stable band and still drives up difficulty over time, which is what you’d want if you care about genuine reasoning improvement rather than reward hacking.

The bigger question is how far this paradigm can stretch before the supervision and infrastructure costs dominate again. R-FEW avoids large labeled datasets, but it does assume access to a fairly strong base model, a non-trivial human anchor set, heavyweight judges for verification, and enough compute to run many rollouts and GRPO updates. It is also not obvious how robust this remains when you push beyond math and exam-style benchmarks into messier real-world tasks where ground truth and reward design are far less tidy.